Architecture should be a bridge between the larger issues and the smaller acts that a lot of people can do in this life

‘When a young man becomes an architect or just decides that he wants to be an architect, there is one thing, that he wants to leave a trace. That’s what should be a little bit rethought, that maybe, the next generation should learn, or our generation now should learn how not to leave a trace.” – Balázs Csapó, President of the Budapest Chamber of Architects., Moderator of SHARE Budapest 2020, during the final debate of the day.

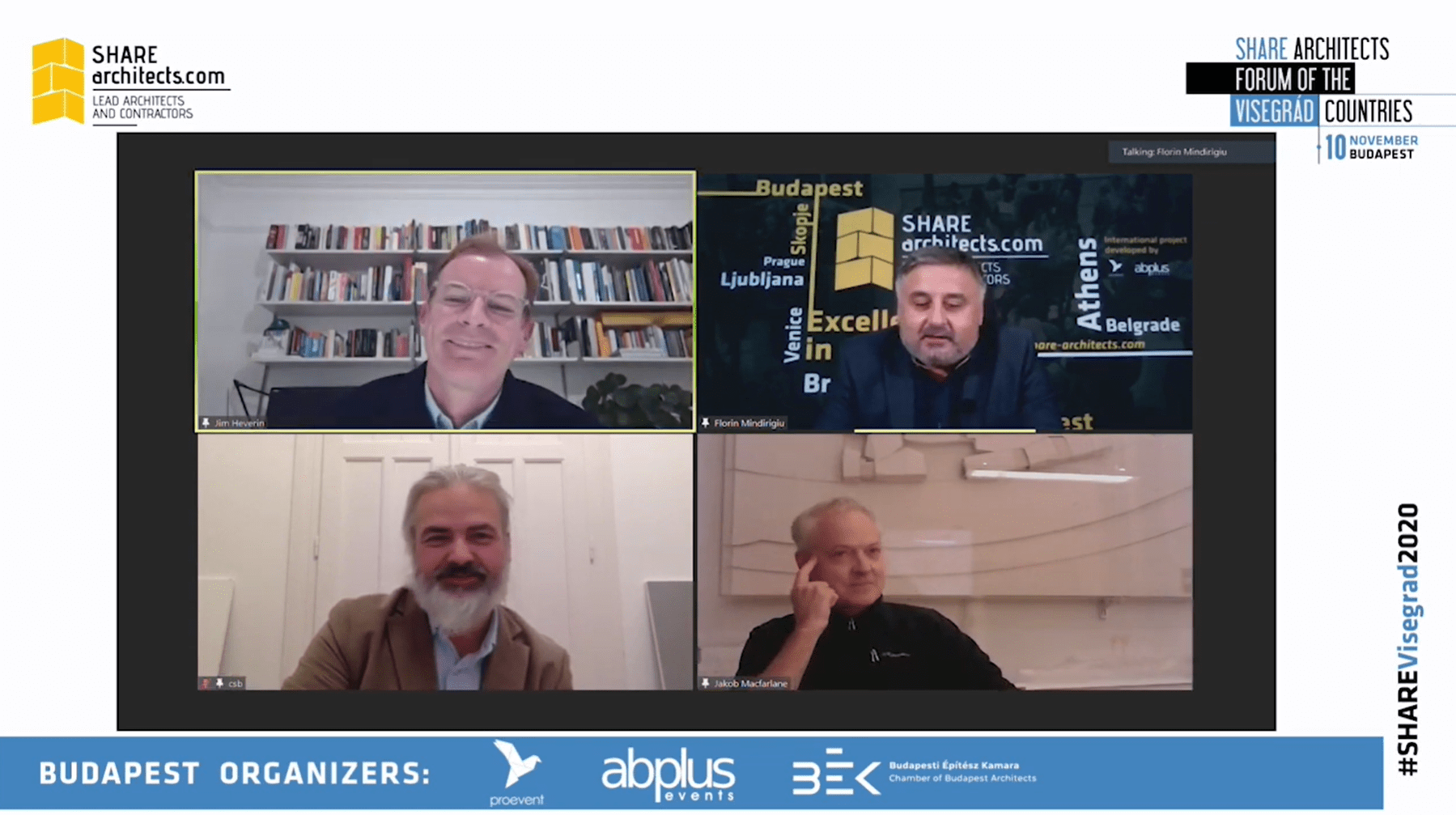

The day dedicated to Hungary during the SHARE Architects Forum of the Visegrad Countries has ended with the presentation of a special guest arch. Jim Heverin, board director Zaha Hadid Architects, and provocative exchange of ideas between the special guest, arch. Balázs Csapó, arch. Brendan MacFarlane, Partner JAKOB+BRENDAN MACFARLANE architects, and Florin Mindirigiu, co founder SHARE Architects.

We share with you in the following paragraphs the exact transcript of the discussions that framed some of the following issues:

- How globalism can lift the poverty problem to a new level;

- How high-end architecture can somehow drip the efforts down to the lowest levels of humanity;

China’s new net-zero emissions target for 2060; - Architects turn into creative engineers;

- How the young architects look like;

_______________________________

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL

_______________________________

Balázs Csapó: I’m really thinking about your starting point on how globalism can lift the whole poverty problem to a better level. The buildings that you have shown us are really the other end of the world in this way. How do you think that this high-end architecture can somehow drip the efforts down to the lowest levels of humanity? This kind of building is expensive.

Jim Heverin: Which ones? They’re not all expensive, and they’re not all at one end of the market. I think we have done a range of buildings in a range of different contexts. I think everybody deserves architecture to do more than just be some functional object for shelter and a place to sleep or a place to work. We’ve done a school in one of the most deprived areas of London. There’s a whole list. Our whole portfolio was built on public projects won through public open competition tenders. It wasn’t something that we were some kind of luxury stars, and we still do this and this is our still main interest.

Our main calling card was always to try and open up buildings, but as the building in Cincinnati, or Wolfsburg, or the Aquatics Center in London, all trying to open them up to engage the public and to make buildings more accessible for everybody. Then, of course, from there, we springboarded to doing more private clients. It’s still a fact that some of those are private commissions, but we are still in interest in public engagement. I think I showed we’re doing offices at the moment for OPPO. OPPO employs thousands. of ordinary people.

That’s one way of looking at it but also we’re doing these technoparks and urban regeneration, not only in China but in Budapest, in Prague, in London, in Bratislava, and we engage with different cities and everything is an opportunity for us. Architecture shouldn’t sit back and be timid and be less empowered to try and engage with people and to create dynamic spaces, which are contemporary and life-affirming.

Balázs Csapó: The question is if we can make an advanced architecture, will this be, let’s say, a developing force for the lower part of the architecture?

Jim Heverin: You would hope so. I had a client yesterday who put it quite a good way in terms of the proliferation of technology that if you imagined at the beginning nobody had mobile phones or Apple phones and now so many do, and that luxury becomes a necessity is a way that he put it. I think it’s age-old, centuries-old, the connection between architecture and power and those with money and those who commission, it’s, obviously, we would wish many things.

We try to show, we try to push clients that even if they’re doing a private project that there is a civic aspect to it that they are aware of the civic aspect, and I think the whole sustainability aspect of that is now becoming the key civic aspect of whatever you do. In terms of having good quality housing for everybody, of course, we would all wish for this, but we’re not being asked to do that. We can only respond to what we’re been asked to do, and we have engaged with the subject if that’s the question.

In some countries, it’s part of what you do. In England, it’s part of how social housing is delivered, it’s part of the price that a private developer pays, in different countries it’s different. I’m not sure if that answers your question. I think for me I know it’s a big statement about globalization, and I’m not an economist, but I do see this kind of purist argument and reductive arguments against aviation, not that I’m going to stand and fight to the death on aviation, but there are complexities in all of these parts of globalization.

It’s quite self-evident when you see the change in parts of Asia, what globalization has done for them. Of course, there have been costs to that. Costs mainly in the West, but I think that there are factors involved there, and all my point was that we shouldn’t get so purist about this. We can’t afford to be purist. We need to engage with clients. We need to engage with cultures and people and help them by small steps, and we’re not going to get there by big statements, which is just going to lock us out of the room, and we’re not going to be asked to be involved.

Balázs Csapó: Yes, absolutely. I have an idea that it is sometimes too much that architects try to achieve on our own, I would say. A lot of responsibility lies on the client’s side. Maybe they should understand what the impact of the building truly is. Maybe this is the turning point where we can reach a better outcome.

Jim Heverin: Great. Absolutely. I think for certain, we have been at fault in the past in not raising the subjects and not showing the data and showing the consequences of decisions, but there is also a context within which a client sits, it has to worry about its investment, about its future tenants. I think the most optimistic thing, and I know it’s done for political reasons, but for China to state that it’s going to be net-zero by 2060, and for what is effectively becoming the largest economy in the world with the largest population, that is a humongous statement of intent, and it will flow down into the built environment in terms of what they expect from it and how they expect to achieve it.

I think we’ve seen that with the way that they’ve delivered high-speed rail and all of the infrastructure and the leaps and bounds with good stuff nations come around. Out of that will flow many other political– Japan also recently started to talk about similar commitment. I think all of that is really something to be celebrated because it starts to put– Of course, we would all love a statutory requirement that makes it absolutely impossible for clients to do anything but the right thing.

At the moment, that doesn’t exist, but we are starting to see it, hopefully with large countries like China really seeing the opportunity and the commitment towards, and particularly, on the net-zero commitments that needed to be made. Actually, I would say now the onus needs to come back on to the West to be making similar commitments because I don’t see them at the moment.

Balázs Csapó: Yes, absolutely. This is an interesting situation, and China takes the lead towards such a unique question. You will think that China would be the last one to make such a commitment and now is the leading one.

Jim Heverin: I agree, but I think we have seen by just working out there that once they make these decisions they really start to implement them. Of course, you could implement this in many different ways. There may be as much detail to be yet sorted out in terms of what they mean by net-zero and how they get there and how much offsetting or compensation is going to be involved or how much nuclear energy is going to be involved. Of course, probably the best performer in the world is probably France, isn’t it? Because of their complete domination in the market with nuclear energy.

I know it’s not straightforward, but I think China for all its faults, it has immense ambition and optimism, and it has immense ability to turn and suddenly face a direction and start implementing. I think that given its stature, its growing stature in the world, particularly that it’s turned to this issue, without knowing exactly how they’re going to get there, I think that’s still an immense statement and something to be really welcomed.

Brendan MacFarlane: I like the presentation. Obviously, you’re talking the same language as what we’re trying to do here in Paris. That’s why we called our presentation adaptable city. I think a lot of the points that you’re making are very good points. Architecture is not easy. Ironically, it’s almost sometimes you wonder whether it’s almost counterproductive towards meeting all of these goals. One would think maybe the most nonpolluting thing is to actually not build. Of course, I think it’s extremely difficult in a way to put all the answers, trying to get all of them together. Your presentation shows that.

What’s interesting in it is that you’re showing what you’re trying to do and what you’re trying to aim for and the different concerns. Today, as an architect, I think for all of the architects in the world, we should absolutely be looking at all of these issues in our own practices. There are contradictory issues. There are challenging issues. None of us has come up with– In a sense, we’re coming up with bits and pieces of answers.

One’s aware of that in the presentation, I’m aware of it in our own work, but I think these challenges are the challenges of right now and where we’re headed. I think it’s vital that the architects of the world, really start to look at these issues completely seriously, and use them, not as a negative thing, but as an extremely potentially creative source of architecture. Anyway, I just wanted to add a kind of answer from France, from Paris, and commend the presentation as well.

Jim Heverin: Thank you. I think I wanted to be at pains to point out that I don’t have the answers.

Brendan MacFarlane: Exactly. I think that’s where– we are all there. We’ve come through a period of a lot of formal, in a way, experimentation in architecture. We have come through a period of incredibly rich language development and being given incredible freedoms, and abilities, I should say, capacities with the digital revolution. We’re in a different space today, and it’s a refinding space right now. I think that’s what we’re all aware of.

Jim Heverin: Yes, couldn’t agree more.

Balázs Csapó: It seems obvious that we won’t have an easy answer.

Brendan MacFarlane: No. [laughs]

Balázs Csapó: Maybe further.

Brendan MacFarlane: That’s the challenge because if we did have an answer immediately on the screen, you wouldn’t be placing the question and we wouldn’t be putting these issues out. I think that’s where we’re at right now. There’s a lot of challenges out there and we’re trying to come up with answers. It’s not easy and it can be contradictory and very challenging, and I think that’s where we’re at hence your question. The exciting thing to say about all of that is it’s actually a very experimental moment. I think in architecture, we should totally take that as a very rich, very interesting moment. We should really be taking that in a very positive way.

Jim Heverin: Exactly. I think architects are always complaining about their lack of agency, and looking back in the past and believing that architects in the ’60s had a particular agency and that we no longer have it. I agree completely that this is a real opportunistic opportunity, but I think we need to talk about it as a positive thing. If we get too puritan– I agree with this contradiction that if you didn’t build anything you wouldn’t be creating carboned impacts. The fact is we are going to keep growing as a population. We are going to have to keep growing as an economy in some form, and we all want to keep living and affording things and doing things. That’s the reality that has to be factored into this.

Brendan MacFarlane: It’s absolutely right, your whole discussion. I remember being in Oslo on a conference and being indirectly told that if one built out of concrete, it was a crime.I cannot agree with you more on this. Concrete is an extraordinary material. It’s a modern, contemporary, and will be in the future material. What’s interesting is what we’re doing now is we’re challenging it as a traditional– the way of using it or creating a lot of pollution in making it and we’re challenging it with green versions of the concrete, recycling. There’s a lot of interesting experimentation. It’s not all there right now, but the material is not going to die overnight, and its use, we should not think that it’s going to be put to the side. I think your point is extremely good on that. I would only second it.

Jim Heverin: It’s interesting, actually, when we did the Aquatics Center in London, and the structural engineer was talking about the use of GGBS, you suddenly discover that there’s this whole byproduct, been piling up in Cornwall, that came from the potteries industry, which was good. It’s called the Cornish Alps, and it’s all this fly ash that has just been sitting there waiting for our use. There must be so much more experimentation and technology that can turn waste products into useful materials that we can use in our built environment.

Brendan MacFarlane: Absolutely. That’s what’s interesting now because we’re asked to account, accountability, as you say, and it’s done through calculations. We never had to do this kind of thing before. It’s good. It’s a good thing. It takes a lot more work. In doing so, I think it will help us also experiment and find new ways of making architecture.

Jim Heverin: Absolutely. Turn us into engineers, won’t it?

Brendan MacFarlane: Creative engineers.

Balázs Csapó: Or ecologists because there is an issue. If we put a lot of engineering work to decide whether to keep one material or to keep it and throw it away, now the reality in my practice is that it’s still cheaper, for example, to completely get rid of stone pavement and build a new one, bringing the materials from example, China or whatever, it is still cheaper to get totally new material, and it is stone, so you could reuse it.

Brendan MacFarlane: Have you been asked to do a calculation based on carbon footprint bringing it from China to Hungary? Have you been asked for a calculation based on reusing local stonework in terms of local employment, keeping resources close to home, et cetera? Have you been asked to give those to the client and show what’s better in the long term?

Balázs Csapó: No, not yet.

Brendan MacFarlane: My hunch is that, and that’s what we’re really saying here, is that the architect now is asked for those calculations. Certainly, our clients in France are asking for that accountability, and it’s becoming a huge issue. I think in the long term, those calculations, if you really look into them, in their full implication, you find that China doesn’t look interesting, and you find that the local market looks extremely interesting.

Balázs Csapó: If you sort out the priorities, absolutely, yes.

Brendan MacFarlane: That’s a very good example of where I think we should absolutely be heading. If we’re not doing it, other people are. It’s not just the architects.

Balázs Csapó: Okay. That was quite a good.

Jim Heverin: Yes. Thank you.

Brendan MacFarlane: It was fun.

Florin Mindirigiu: At the end of the conference, traditionally I have a question for you. What is your message for the young?

Jim Heverin: The world is theirs. They have everything to look forward to, and I think it’s an amazing moment. When I was entering college, all the pessimism around the Cold War, I wasn’t that old, at the end of the Cold War and into recession. I think it’s similar in the sense of there potentially will be some type of dip coming, but as we were just discussing, there’s a huge moment of change coming for our industry and the world at large. They will be the future leaders of this. It’s a real moment of ability to participate and to make that change.

Brendan MacFarlane: I think the same thing and there’s two very recent things that have happened in the last couple of days. We woke up and found that we have a 90% effective vaccine that’s been developed. That’s pretty amazing, and that’s pretty exciting. That’s a short-term thing, but still, it’s an extremely interesting thing because it represents a medical breakthrough in the way that we’re using reworked DNA to fight the virus, and that’s never been done before in the history of medicine.

It represents a new breakthrough in the way we are using science and technology to come up with an answer in six months, which is an incredibly short period of time to come up with a vaccine, which apparently is 90% effective compared to what needs to be at least 50% effective. I think that’s an incredibly positive foot-forward in a period when we’ve had a lot of self-doubts, doubt as countries, doubt around the world. Combined, I would say that’s a great message about, yes, we need to pay attention to the science. It’s a period I think we’re entering into which is hence the whole discussion on calculations and accountability, using the right materials.

Anyway, I think that’s a positive short-term message, which has big implications in terms of the right use of science and working across– Bringing all the talent of the planet to work together. That was an American-German project but was using other cultures to work on the calculations. I think it’s an amazing trans-national project that came up with a vaccine in such a short period of time. I think the world in terms of architecture, we’re heading into an incredibly productive period, which was alluded to a little bit in this last talk, which is why I liked it as well.

In architecture we need to be working together, we need to be working across cultures. It’s one culture, it’s not a separate series of countries. I would like to then add that the results of the American elections, because I think that would be another thing which has just happened, let’s say, in the last few days, which I think is also incredibly positive. I think two positive things happened on the same day. One is the new transitional government in America had their first meeting on COVID and on the same day we had the announcement that there was a vaccine. I think they’re great steps forward. It’s not about politics and it’s not about medicine, it’s also very much about architecture and your future.

Florin Mindirigiu: Okay, thank you. Thank you.

Brendan MacFarlane: Okay.

Florin Mindirigiu: Balázs.

Balázs Csapó: To have the same question to be answered?

Florin Mindirigiu: Please.

Balázs Csapó: Well, I think that it is quite clear that everybody wants to leave a trace somehow, so when a young man becomes an architect or just decides that he wants to be an architect, there is one thing, that he wants to leave a trace. That’s what should be a little bit rethinked, that maybe, the next generation should learn, or our generation now should learn how not to leave a trace.

Balázs Csapó: How? Stay home and stay healthy, but it doesn’t mean that you should stop living. I’m not talking about that. All this effort that drives people to do something should be placed on an ethical basis. I think now more than ever, architecture should be a link, bridge between the larger issues and the smaller acts that a lot of people can do in this life. Maybe this is my message.

Brendan MacFarlane: Nice message. Good message.

Florin Mindirigiu: Thank you.