Jim Heverin on the future of urban living during SHARE Budapest 2020: I think globalization is a clear necessity for lifting many millions of people out of poverty.

Board director of ZAHA HADID, arch. Jim Heverin has closed the first day of the special SHARE edition of the Visegrad countries with a captivating lecture and afterward debate on “The future of urban living”.

With a main interest in cities in evolution and changes in the role of the architect, arch. Jim Heverin started from the premises that we shall hope to see significant changes and quick changes in our cities provoked by the COVID-19 pandemic. With a focus on the acceleration of the process, he then took the audience on a guided tour around the works commissioned by the office in a pandemic era and how each country has adapted to the new environment – walk cities, cycle cities (China), 15-minute city (France).

Throughout his mapping of the world, he has opened discussions and sparked reactions on important issues such as climate crises, carbon footprints, hybrid materials, and finally a transformation of the architect in a creative engineer – “We are now duty obliged to have this conversation, no matter how difficult it is in all different regions with all clients”.

_______________________________

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL

_______________________________

Jim Heverin: Future of urban living. I was thinking about this, obviously, living through COVID, as we all are. It’s obviously been quite dreadful for a few reasons. I think it also gave us the real opportunity to experience and see our city in a very different light. Here in London, in the first lockdown, we experienced roads suddenly without any traffic. Where I live, I was able to walk freely across the streets. Suddenly, I felt I was in Holland, or in Copenhagen. It became much more civil in London.

I think it gives us a glimpse of optimism. I think I’ve seen through Europe, some countries or some cities, in particular, grab hold of this opportunity, and really use this as an opportunity to change our cities. In particular, traffic and cars have really turned our cities into something that needs to be addressed. In London, we have huge issues with air quality, pollution, due to the density and quantities of cars. We have significant issues in terms of just safety and how we get about our city. I think it wasn’t only that, there were many other levels to it. I think we would all like to see out of COVID come to a real opportunity for change.

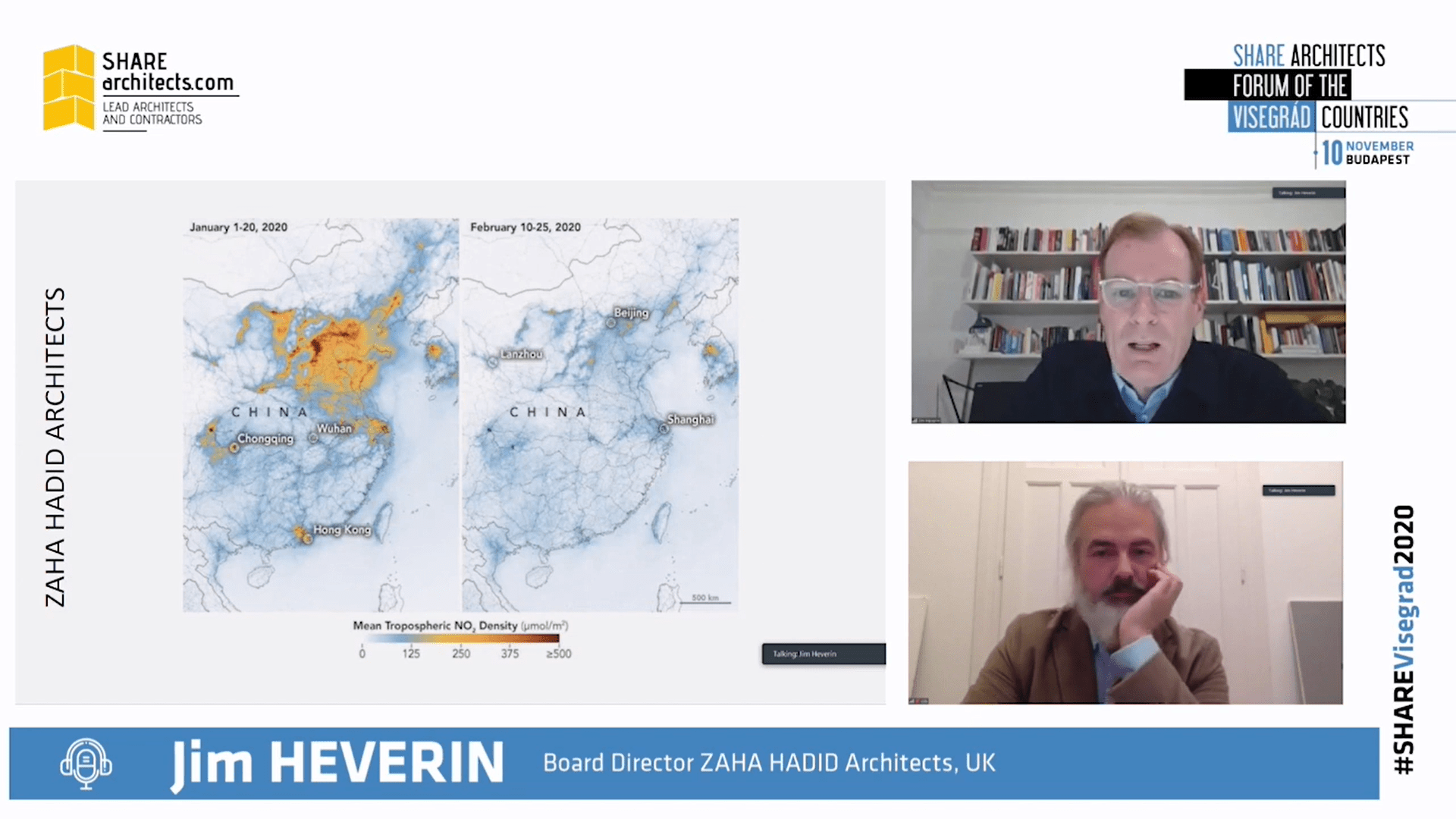

It’s interesting that a lot of conversation has been given, this is just a diagram, on the left, showing the pollution levels pre-COVID in that belt around Beijing, this industrial heartland of China, and what happened when all of that production stopped. Then that led on to conversations and dialogues, that this was a matter of choice and not a necessity. Something I wouldn’t agree with. I think globalization is a clear necessity for lifting many millions of people out of poverty. It’s a complicated issue. Of course, what was great, is it demonstrated the cost in terms of carbon and pollution. That’s something that China is looking to address, and something that we all need to start addressing in a much more constant fashion.

This diagram is really just showing, obviously China first, then Europe and the States and how that necessity will come back to in terms of the returning-to-work and the pollution levels will go back up and our way of working in our occupation. There is obviously a lot of dialogue about whether this throws significant doubts on the idea of towns and cities, I don’t think it does. I think cities have faced these issues before; whether it was fire or disease, going back many centuries. We’ve always looked and found solutions and overcame it.

Out of this, you would expect, as I was saying, this optimism and this hope and the real political momentum to see significant changes and quick changes in our cities and not this constant lag and this constant need to compromise and dilute everything to the point of having no effect at all. I would really hope for an acceleration. Again, I think, for obvious reasons, a single-party state, that China is really going to be showing the way. I think for us, we have seen immediately a pick up. There’s no sitting back in China. Luckily for us, we are very well placed in China. We have an office in Hong Kong. We have an office in Beijing. We’ve been there for the last 20 years.

Like the last recession, this recession again, the Chinese, for them, they jump in immediately, becomes a stimulus in terms of pushing capital projects, and this is one. These are commissions that we have picked up in China in the COVID period. Some of them began beforehand. This is a stadium for the next Asian World Cup, later in the 2020s. It’s in Xi’an, this historic city. It’s based on a temple. It is showing the confidence of China.

We’re also doing– we got this commission for OPPO. I don’t know if you know OPPO, a large telecoms/mobile manufacturer in China. This is a very extravagant office building in Shenzhen, which is really expanding at such a phenomenal rate. For this project, of course, this is not the kind of standard in terms of replication. This is a client looking to do something really unique, pushing the boundaries of glass. These will be insulated units. They will be double curved, and single curved, et cetera.

We’re also doing a lot of other types of work, which is much more rationalistic and repetitive, and efficient, but also looking to capture the kind of key characteristics we see in urban development in China, which is optimism, which is looking at mixed-use. This is a technopark. We’ve done several of these current designs, all progressing at a pace, looking to create mixed-use urban quarters, where you’re mixing, creating office spaces, living spaces, retail, recreational spaces, and all on the basis of everybody coming together in this new urban quarter, which is very much based on density.

Also for us in terms of how we’re responding in terms of design, the briefs are coming forward. We’re also focused on the humane aspects, the incorporation of nature. These are walk cities, cycle cities. They’re very human-focused, and the scale, even though the density is there in the background, it’s mixed in the two. We have done similar work elsewhere. This is a commission we picked up, one lucky to win, in Budapest. Also, mixed-use on the edge of the city; mixing residential with office and retail.

All of this, I think, is really for us, looking at the city– I think I just want to talk today, not only about the subjective aspects, because this is what we always talk about, what is the narrative, what is the poetics, how we approach the scale, the massing, the materiality, why this is appropriate, or why this is more than just pure function, how it gets to the emotional level, but there’s obviously, a bigger crisis facing us, which is the climate crisis.

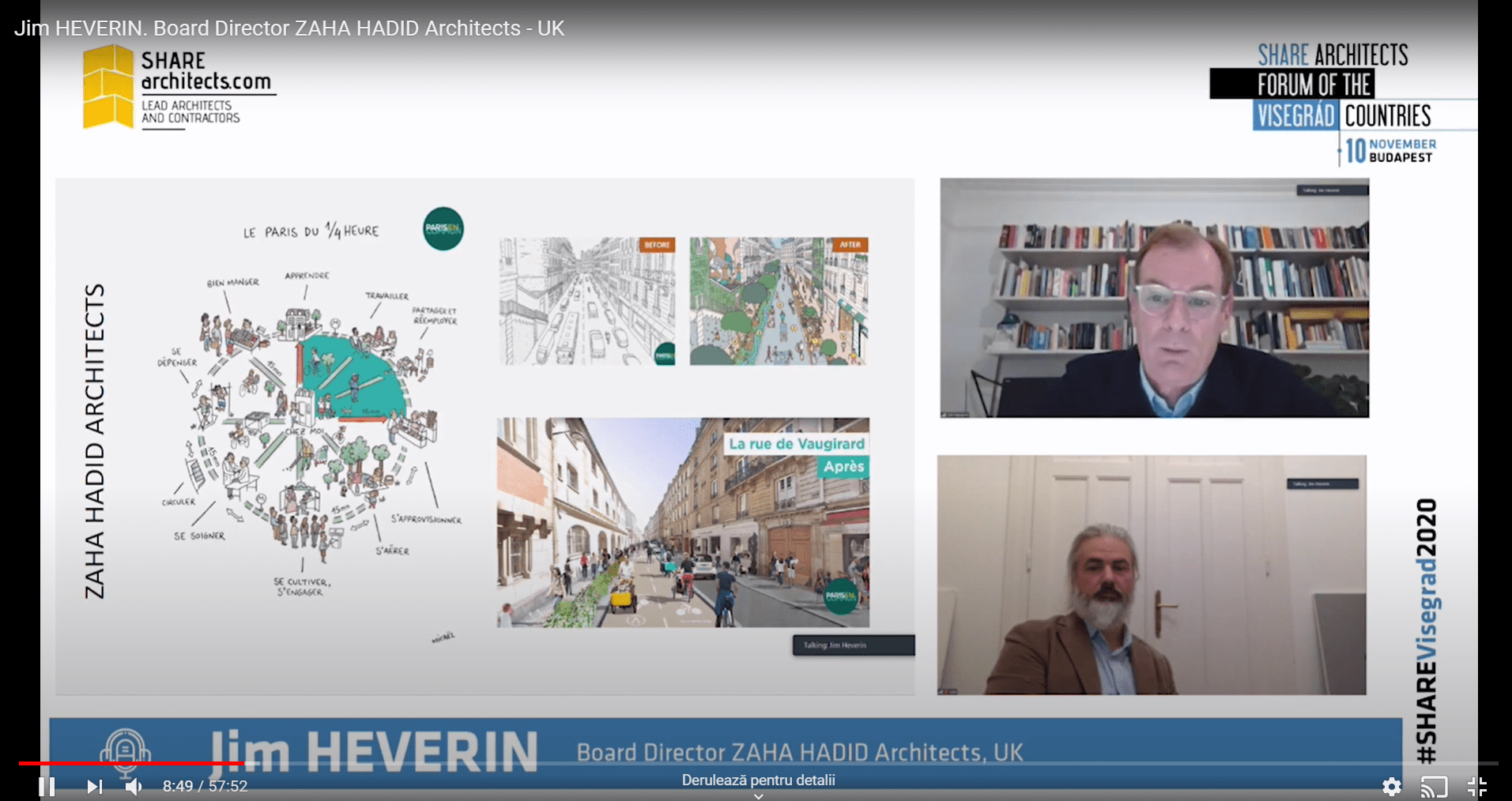

I think for once architects can talk on an objective basis from project to project. It’s something that we are starting to have to look at as an office. We’re obviously looking at it from a point of view of an office that needs to do a lot better. I’m not in any way pretending that we are an exemplar, I don’t think very few are. It gives me great hope when I see the mayor of Paris really grab the initiative out of COVID, introducing the 15-minute city, which I think we all know about, but really acting on it, and really implementing it, and really looking to go and start to change Paris. I think there’s real widespread support for it. I think I will find that throughout many cities.

The only reason this hasn’t happened in London to such an effect is because of the way the London mayor is financed. Coincidentally, one of my partners, Patrik Schumacher, did a study based on walking and how certain walk distances could connect the city together. Again, what’s really impressive about Paris is the fact that it’s almost going out in the night, transforming roads, which were two lanes for cars, immediately taking over half of it for cycle lanes.

I think this really shows you this kind of spirit, which we really need, to tackle this and to turn it into a positive. This is positive for how we occupy and get about our cities. We really need our politicians to work with us and take this moment to work with us to change our cities. I hope we’re all aware of the UN IPCC report calling for action by 2030. We think it’s hugely significant that China is putting its weight into this and talking about being net-zero by 2060. We will in all those projects start to see this become more and more of an issue in China, and hopefully, we see this elsewhere throughout the world.

It’s uncontestable the amount of work that has to be done, and this is just looking at the splits between– Clearly, most of this is in the production of energy, and then obviously, you go on to agriculture. You can see down at the bottom the energy used in buildings at 17.5%, which if you add in the extra energy that’s used in buildings– I know sometimes this 40% is used against a built environment. I personally find this a little bit misleading because actually half of that is plugin loads such as cooking or the computers. The other half or the other quarter of that is actually rail and roads.

As much as I wish to beat up architects and contractors, they can’t be beaten up for all of this. They’re still significant, and what’s more significant is obviously, about 6% is new builds, about 17% is due to the existing fabric. A lot of focus needs to be put on that, to not be demolishing buildings, and to be refurbishing the existing buildings that we’ve got to a higher standard. It’s for all of those reasons that we signed up to the UK Architects Declare, not because we thought about a greenwash or we thought was good for PR, none of those things. We thought about it, really to create another stick for which people can beat us. Because there are plenty of sticks already, but this one we actually believe in.

This one, it’s for us really to be constantly reminded that we need to do better. This is the only reason we added our name to this, and any profile that we’ve got is really to push ourselves to do better. From that, obviously, we’ve started to undertake a review of our past projects, our current projects, and our future projects. It’s quite clear that all of these certifications are no longer ambitious enough. What has been quite good is this document, and I’m sure each country has an equivalent, but the RIBA, for once, actually produced a succinct, short, four to six-page document that actually outlines clearly what we need to do, and it’s clearly on operational energy and embodied carbon.

On those two factors and all the rest of the stuff that you get sucked into on lead, about biodiversity, all of this is, is really, really a secondary or tertiary or way down the list, compared to these key carbon areas of consumption. I would really recommend this document because it’s very, very clear. For us, we’ve started to look at this. One of the issues for us is that we work in a diverse range of regions, from Europe to Asia to the States, et cetera. Of course, all of that could give us an excuse. We could constantly say, “Well, the statutory requirements are unfair. We find it very difficult to persuade clients,” and all of that is true.

This is universal. The climate crisis is a universal matter that goes beyond any site boundary and we are now duty obliged to have this conversation, no matter how difficult it is in all different regions with all clients. These are some of our projects and we just finished in the last year, but each of them, we’ve done, we’re looking at them, and obviously the first one is a large airport we produced, finished in Beijing. I know there’s been a lot of criticism of– I think mainly just within the architectural community, but I could be wrong, of aviation and architects’ involvement in aviation.

I would make the argument that aviation is key to globalization, it’s key to lifting people out of poverty. Aviation will continue to expand, and it needs to address its carbon footprint. I don’t believe in this purist point of view that you start to cut off areas of our activity and say, “No, we’re not being involved in that,” and then you remain in your ivory tower and you somehow don’t engage with the world. I think we don’t believe in that, but we do believe that obviously, aviation has a lot to do.

The same with national and international sporting events. This is the stadium we just finished in Qatar, a beautiful thing. Part of a beautiful football tournament, and we will still want these types of tournaments where people come together and congregate. As a world and as a community, these are immensely useful for intercommunication. In this stadium, this was a program that wanted to address carbon, it was a discussion. Unfortunately, in the end, one of the key aspects addressing that was not implemented, which was the use of timber.

This is an office building that we’ve just completed in Beijing. I think I’ll go through these quite quickly. All of these. Actually, this project we’ve done for Penta Investments in Bratislava is a good example of a low carbon design, where through what the client wanted to return, achieve, in terms of budget, but also in terms of technique. We were really looking at glazing ratios which are 50/50, so it’s balancing high rise, which obviously has impacts in terms of what you pay as a premium for the structure, but it’s the insulation, and the quantity of glass is kept to a minimum to avoid overheating and the excessive use of cooling.

Then this is just another project we competed in Nuremberg. I’ll go through, with also a project we completed in Hamburg. All of these, we have to get to look at them, particularly from the embodied carbon point of view, and gain, sand, gravel, crushed rock, which is obviously the key aggregates, ingredients of concrete. Again, we don’t participate in this point of view that you could somehow replace concrete with timber, or you could replace this with stone which is a ludicrous argument.

The issue of concrete is just that it’s so immensely successful as a material. It takes local sand and gravel, mixes it with cement, which has to come imported, usually. It’s the success of actually using that and being cost-effective and efficient, and there are ways to address it, which needs to be done. Of course, the starting point in any project is to reuse structures. We see far too much demolition happening. If I just think about the UK, in particular, there seems to be rampant participation by architects to particularly demolish post-war modernist buildings on the pretence of upgrading them for performance.

While this is a project we did in Antwerp retaining a building that looks Victorian or post-century but actually was built after the war. I would really make the argument against any architect who’s involved in the demolition of post-war buildings because it seems to be– We have looked extensively at the use of timber, but there is a degree to which its use cannot– Just from pure efficiency in terms of structural efficiency it reaches capacity issues, and this is looking at glulam and CLT planks. When you start to look at it for offices, where you have long spans, it becomes heavy and clunky.

I would really say hybrids where you’re using steel or concrete and then combined with timber. I know many architects are looking at this. There is a downside to timber, which is that it is something that unless it comes from a renewable source feeds into all of these issues, from deforestation to the urbanization that comes in its wake. Unless timber is coming from a certified renewable source, and unless it’s travelling a short distance from where it is sourced to where it’s been used, you’re just adding up the carbon, so it’s not this easy calculation where you take out concrete and you just throw timber in as a word.

If it’s travelling halfway across the world to get to where it needs to be used on-site, it’s a false economy. Of course, unfortunately, we had a significant fire in a high-rise building, which had nothing to do with timber. Timber is actually going to be one of the main consequences of what comes out of the regulation change in the UK due to the Grenfell fire in 2017, which is very, very unfortunate. It looks likely they will be setting a height limit in the UK of 18 meters, above which, it will become a very, very difficult issue to argue with local authorities.

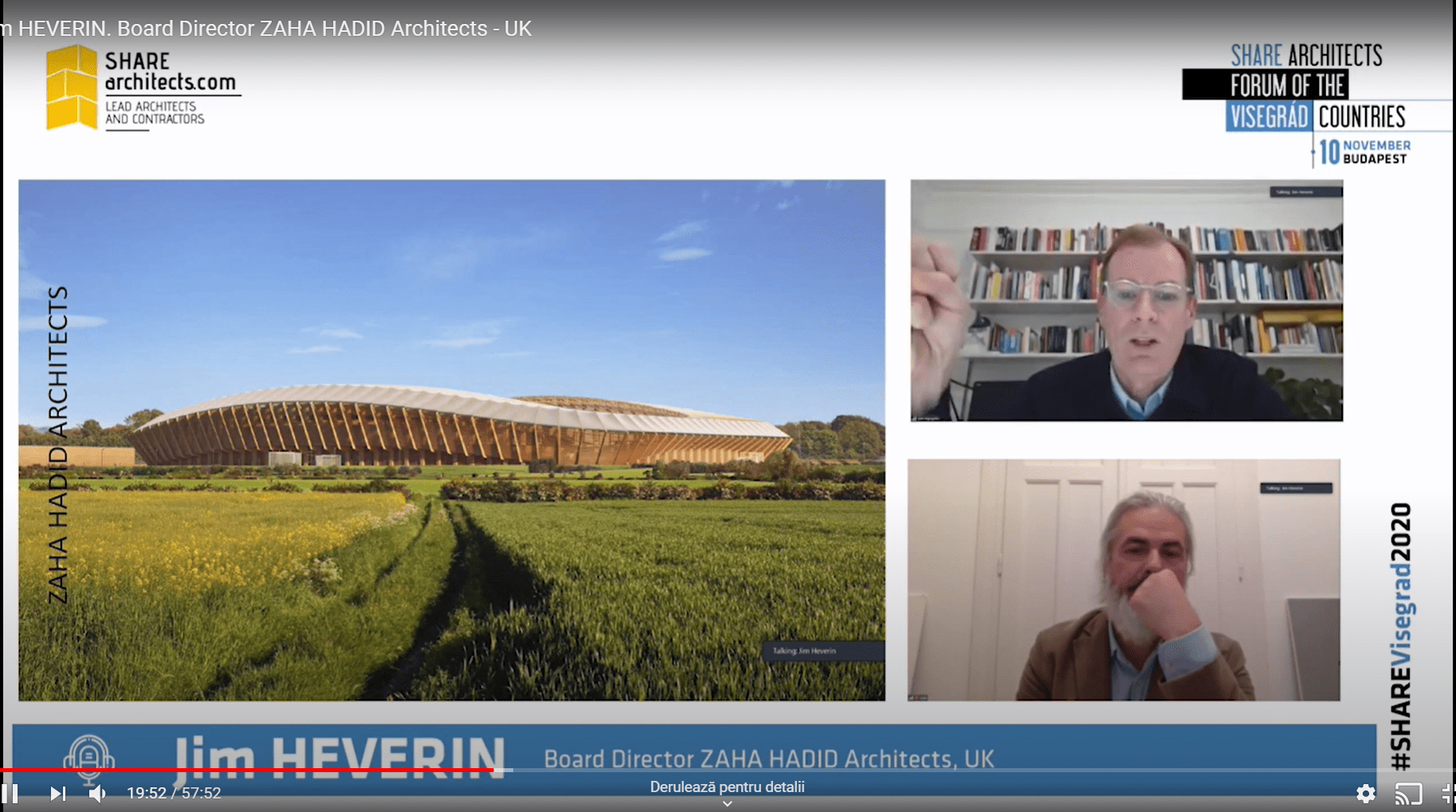

It is an overreaction because on the right-hand side you see this fantastic high-rise timber project in Norway, and it shows you what’s capable, what’s possible, fully fire engineered, and very, very safe. We ourselves have looked at using old timber. This came out of our multiple stadium iterations. We found a client that wanted to do the most sustainable stadium, so we proposed to him why not do everything in timber, not only the roof structure, which is obvious but also the rakers, the seating terraces, using glulam and CLT.

Being able to do so to create something that looks appealing, that’s not wearing its credentials on its sleeve, but actually is dynamic and attractive, but also uses very traditional techniques of the twin column with the beam, but create something– Even this project, which is to be based in Britain, will face issues of where this timber comes from because nobody in the UK makes engineered timber like this. We will have to factor in getting this from France or Australia, or wherever, unless somebody in the UK starts to produce it. I hope they do. At the moment, that would be something that needs to be factored in.

This is part of the low carbon review that we did. On the right-hand side is two of our recent towers, one in Milan, and the one just in, in Beijing. Then we just compared it using the help of Max Fordham engineers with embodied carbon in two landmarks in London, the Leadenhall one, which is the more recent one, on the far left, and then the Gherkin, or the St Mary’s Axe, as its proper name is. It’s a little bit unfair because the Gherkin or St Mary’s Axe is actually a very innovative tower project using atriums, et cetera. It is really just looking at the embodied carbon in these projects.

Surprisingly, we did well in Beijing. The Milan project did best because it used recycled aggregate from the buildings that had crushed on site. There was no transportation and the concrete was made on-site, which is why it did so well. It just shows you if you don’t look at the targets of actually all of these buildings or just about where the two projects by us are just about hitting the RIBA 2020 target. We might scrape in with 2025 by 2030. That really just shows you what’s ahead of all of us.

This is not something that should be the exception or this assumption that if we are to do what the UN is telling us, and if we are to see off this increase, and if architects and the built environment is to do its best, we are going to have to reach these targets for every building, not the exceptional tower in Milan. This is the message that we are taking internally, that this is a huge issue. Of course, like I was saying, we argued the use of concrete has been fundamental to our practice. We believe the very fact that it is so common it is why it is such a contemporary material.

We have looked at using cement replacements. In this case, looking at using GGBS and also using recycled aggregates and very successfully to get the fair face finish. When you strike it, it has this blue hue to it. Over time, it returns the normal greyish tones. This is the first project we did in 2012 using the specification. Now for us, we need to try and use this for every project where we’re using concrete. In the UK, we’ve been able to do so. This is a project we did in Oxford. I think really the challenge for us is to start to persuade this to happen in China and other markets where we’re operating.

It brings us on to the other issue, which is the airtightness and the level of insulation. I think these are key factors of pushing beyond what’s in the regulations and also then testing how you achieve it. This is a project we did in Glasgow. It’s a big shed which is why this infrared camera shows it to be working so well. There are very few openings. On this, we achieved quite a good airtightness, just for the sake of the fact that there were very few windows. What kind of key to us is that going forward, that level of airtightness you’d have to achieve on all types of building, offices and residential buildings, with many, many types of openings.

Of course, the key to it is the quality of construction, the force, accuracy that goes into the detailing, and likewise into the construction, which is why it’s so interesting to see the offsite manufacturing discussions. Of course, the frame and the structure are where a lot of the energy is used. This is a similar project to Milan that we completed in Marseille with a double facade. The double facade unlike the Milan tower was not a ventilated facade. This is Just a naturally ventilated outer glazed screen, which significantly cut down the solar gains, and allowed us to use chilled beams, which is the first time that chilled beams have ever been taken from Northern Europe and used in the Mediterranean.

Again, just following through in terms of this has been completed since ’15, and we’ve been back and the chilled beams and the overall energy consumption– the client is really very happy with both how the chilled beams are working, the double facade and the level of reduced energy that they’re having to pay for and use in the building. It’s something that we took on to a project when we have a commission to do a towering bank, the Central Bank of Iraq, obviously, even in the more extreme climate than the Mediterranean, and looking at using fins to reduce the amount of solar gain while at the same time balancing bashful daylight.

It’s really the analytical side to this, understanding the metrics, being aware of this, and feeding that into the design. It still didn’t stop us from creating a very iconic, complicated facade, which is on-site at the moment. I take the criticism that this is using too many materials. Again, it is something that we looked at for a project in London is using a kit-of-parts, and how those kit-of-parts could be put together in the most efficient way. The overall kit between glass and precast creates the depth, the shading, the low glazing to solid ratios so that you have an overall low carbon design, but also doing it with the most efficient use of materials.

For us, it’s an overall, constantly moving circle of all of these components. I think this, for us, at the moment is something that we’re really given a lot of thought to and self-criticism to do a lot better on this and to take this into our projects as we go forward. Thank you.