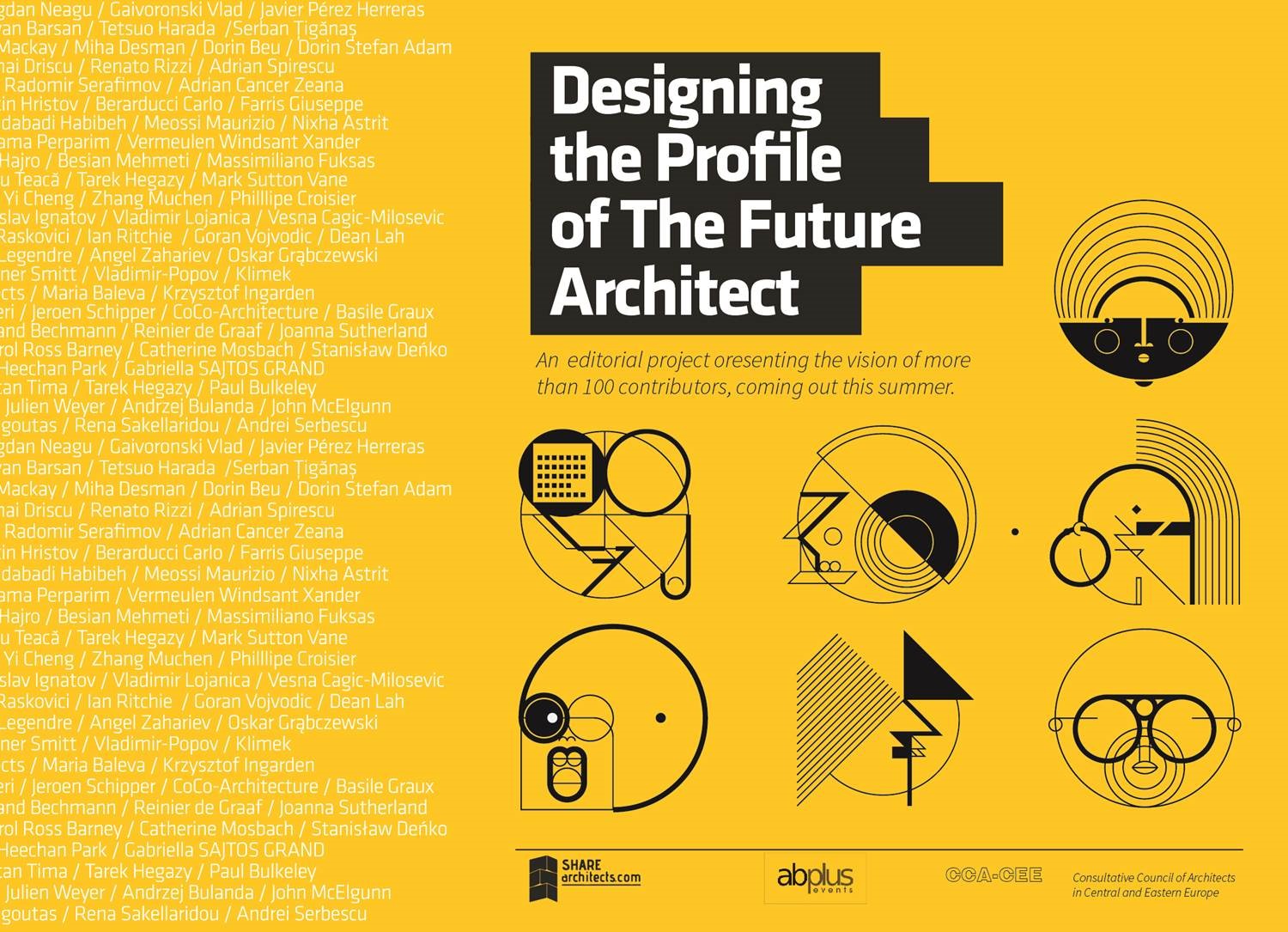

Announcing “Designing the Profile of the Future Architect”, our editorial project that highlights 100 international contributions, coming out in 2019

Over 100 contributions from the 2018 repertoire of discussions with our guest speakers will be gathered in a volume answering the theme : “ Designing the Profile of the Future Architect” . This international editorial project initiated by Eusebia Mindirigiu via SHARE International Architecture Forums -that are organized every year in 10 locations from Eastern and Central Europe- will address the most challenging issues and challenges of the profession. The synthesis presented below is an excerpt from the book that is coordinated by our editors, Serban Tiganas -general secretary of International Union of Architects and Andreea Robu-Movilă, publisher of SHARE.

We have challenged around 100 architects and designers to anticipate the needed or resulted profile of the architect in the future. To have that it seems important to understand the situation of architecture in the present time. So, what is happening? What I happening with the world of architecture, with architects and how the present is perceived here and there, where architects are practicing? What is happening in general and in particular? You will find a lot of direct answers or explanations. The manifestoes are providing filtrated essential visions while the interviews are releasing more spontaneous reactions to those questions. Of course, not everybody is seeing the determinations of the present the same way, but we can notice convergences.

Many authors of the manifestoes referred to the actual situation of architecture in relation with the world and to the profession of architect nowadays. Most of the interviewed were asked about the situation of architecture in their countries or where they are practicing, in case of export. At all we observed references to the present in 14 of the manifestoes and in 37 interviews. The situation of architecture and architects was commented for the following countries: Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, France, Greece, Germany, Holland, Hungary, Iran, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, Thailand, Turkey, United Kingdom and United States of America. Some of the interviewed architects are practicing in several environments having the possibility to make comparisons.

The world is changing, no doubts. New global problems are getting the stage of being crucial for the future of human civilization. The Anthropocene is the era we live, when the destiny of the planet depends on a single species, humans. Architecture is the frame for this world. If the world evolves, architecture is demanded to respond to new challenges without forgetting to balance the future with the past. Architects are not the decision makers, but their competence and involvement may be relevant. Big firms and very small practices, even sole architects are responding to a global market with local influences. Some have tremendous success while some are struggling. Consumerism, neoliberalism, populism and political behavior is affecting even determining architecture in most of cases. There are lots of improvements and also deteriorations of practice environment and of the quality of its results. But let’s look at our contributors’ opinions.

Present times are characterized by several dualities like nature and city, global and local, public and private. Ian Ritchie refers to one he considers determinant for the state of architecture. “I think there’s a duality in the architectural world at the moment between the technology-driven explosion of changes in the process and theory of architectural design and fabrication, and our social responsibility as architects.”

An increased complexity is surrounding us at the age of information. Perparim Rama is describing the situation of our time: “Today, we can be anywhere in the world and access information we need to conjure any types of proposal. Today, we have access to information and proof that the environments we live in have a direct impact on our behavior. We need, as architects, to ensure that this impact is a positive one for both, the humanity and the environment we live within. Today we have technology able to extract information directly from our body and our environment. Today we have the ability to streamline the two, pretty much fuse the two and understand that our bodies are vehicles which can be better maintained in order to aid us to live a more fulfilled life.” And he also anticipates the future to come.” Today we can witness the emergence of a new kind of economy, the shared economy. We do not need to own anything; we can share everything through membership rather than ownership. By default, this provides each and every one of us with more, and infinite choice.”

It is an optimistic perspective on technology. Julian Weyer is questioning the opportunity. ”Architecture is a framework for life, and as such an inextricable part of the concept of society. Architecture is often seen as the expression or product of our cultures, but it is also the very breeding ground for culture itself – the proverbial chicken or egg causality. When looking into the world today, a world of accelerations – populations, conflicts, communications and distractions – where does this leave architecture? Will it be equally transmuting from the familiar towards the unfathomable, or will it the opposite – an anchor of permanence in the midst of a landslide of exponentially growing complexity?”

Too much information means also not enough time. Marija Simović and Petar Simović are complaining. ”The tools that are given to this profession in this century, the tools of digitalization are demanding that everything becomes faster: the developing of the concept, the delivery of the project documentation. Those skills have lead architecture in one way that can be defined as fast architecture. Augmented hypervirtual reality has taken time from Future Architect to nurture Architectural process.”

The intense pressure of the major changes pushes us to slow down and step back, considers Patrick Meyers. ”In the last 100 years the world experienced a huge growth of population and a major boost in technology. It resulted in a postmodern and global society where the standard living conditions benefited from. But it also had a backdrop; this change was too fast and too distant and unrooted most of the people. Worldwide there is today a tendency in societies to find these roots back again; from global back to local.”

Martin Knujit refers to another duality and states a new role for architects: “We belong to the nature, and to the city. Rapid urbanization changes the world and, as a result, within a few years more people will live in cities worldwide than in the countryside. Under the pressure of urban expansion and changing economic and social conditions, the primary assignment of creating large quantities of housing should shift towards creating quality of the living environment. Within this perspective, the traditional role of the architect has ended and has started to convert into an integrated role spanning across urban planning, architecture and landscape architecture.” Actually, he is extending the role of architects.

Darius Reznek looks to nature and landscape too. “With the enormous challenges facing our world today, from climate change to fast urbanization, architects tend to take on the role of saviors, thinking they can, and must provide answers to these challenges. Specifically, landscape architecture has been charged with a notion of responsibility to tap into its unique repertoire and provide suitable responses to the challenges facing our time. Similar to the promise of the early modern architects, these decades hold the promise of the landscape architect. In this new role we tend to preach about the importance of collaboration, process driven design, temporality and many more similar approaches, often inspired from the natural world. Maybe the only thing that has changed is the preacher, but we are still putting our hopes in a religion of some sorts: The religion of nature.”

But what happened? Is this the result of modernism in form of a massive failure? Everything became too big, losing contact with the individual. Ervin Taci argues on this: “The architects’ challenges in the past, present and the future have been connected to the human scale. After World War II, due to economic expansion and industrialization, cities expanded enormously. Planners and architects were in front of the new challenges. They on block, globally respected the principles of Athens Chart, but unfortunately forgot to design the city extensions and public spaces in human scale. The high-rise buildings with the enormous disproportionate spaces in between them apparently neglected the human scale, desperately losing the social cohesion. Paradoxically, modernism in particular put a low priority for public space, pedestrianism and the role of the city space as a meeting place for urban dwellers. After almost 40-60 years of neglected human dimension, our generation has an urgent duty to transform the public space and to once again create cities for people.” He confirms the concentration on cities and the signs of progress. “In the last two decades the most conscious cities and Mayors are focusing this argument. Urban planners are more and more in the reinforcement of pedestrianism as an integrated city policy for developing lively, safe, sustainable and healthy cities. The strengthening of the social functions in the city space will contribute to social sustainability. City planners are the first, who shape our lives, by reshaping the cities organism. A city that invites people to walk must by definition have a reasonably cohesive structure, that offers short walking distances, attractive public spaces and a variation of urban functions.”

Massimiliano Fuksas is worried about consumerism and points to the human need of emotions. “We buy more, drink more, eat more — more is a quantity problem. We prefer quality. Architecture is about the quality of space. Architecture should improve people’s lives, particularly those of hurried city-dwellers. Building should not only solve practical problems but also give emotions. The architect has a responsibility because what he builds is meant to stay on the earth for a long time. This responsibility engages us with civil society because it’s pointless to develop something beautiful if it does not take into consideration the needs of the user.”

The pursue for sustainability is erasing differences. How to innovate and progress is Stanisław Deńko asking? “Humanity is currently observing its increasing independence from climatic conditions thanks to the advances in technology – both in the application of technical energy-saving solutions and in obtaining energy from unconventional sources. However, this leads to the unification of solutions in the field of architecture, and the form ceases to be the result of the location of the building and dependence on climatic conditions – it is often an end in itself. Attempts to preserve historic aesthetic patterns specific to particular regions executed by architects are often grotesque. Similar changes take place in the design of building functions, in which international standard solutions are clearly dominating; proposals that differ from the established scheme often meet resistance from the ordering party and its advisers. Despite social expectations for innovation, it is difficult to persuade investment managers to take risks and to implement new solutions suggested by architects.”

Arianit Loxha is remarking a possible impasse. “As a paradox in these new times, practicing the Architect’s profession has not become easier on the contrary with the complexity of modern societies (economy, governance…), the global needs (living, working, mobility and technological achievements practicing Architecture it became much harder. We are silently aware that we are on a dead-end path and being unable (or unwilling) to make more long-term planning efforts in order to evolve or change the existing socio-economic models that are dominated by neoliberal doctrines (mainly in economically developed countries). These models do not (generally) attempt to direct or manage public awareness, but they largely based on the philosophy of self-regulating evolutionary mechanisms of the free market. The future, within the propagation of neoliberal discourse, is often reduced in comparison and the shift from the economic redundant mentalities to the advanced ones.”

Xander Vermeulen Windsant is not very optimistic, apparently. “Today, architecture is a profession in crisis. Although the current economic boom generates a lot of work for architects, it, at best, masks a couple of critical issues facing architecture today. If architecture wants to remain relevant for society, or better: reclaim a lost relevance, it will need to deal with these issues head on. Architecture is a global business, in line with the globalized economy. A couple of architects operate in this global context with great success. The work of these star-architects is part of a creative brand identity, sought after by high profile clients who demand iconic projects that are recognized all over the world. But also, in more local conditions, architects are often part of not much more than a local marketing strategy. A specific style of architecture is sought after in order to achieve a commercially interesting distinction. Architectural design has become marketing. Meanwhile, construction companies have automated and standardized construction to such an extent that the role of the architect is often diminished to a very – literally – superficial contribution to the façade design. Marketing does not demand more from the architect.”

We have to take all as an immense challenge for the profession of architect. Let’s look on different places from where our guests come.

FRANCE

Anouk Legendre: “Actually, there’s a huge revolution happening in architecture because the organization of the process is changing. It’s a huge revolution because urbanism, which has changed before for cities and politics, is all based on the choice of a developer to make a certain building. There are big competitions now and we have a big challenge. During every project there is a tandem between architects and developers and they are all in competition to have a big place on a very large site. It’s not architecture anymore – it’s urbanism. So, they need to make associations between developers and different architects. It’s all different now. Before, we were invited to make one building and now we are invited to make a part of the city. Everybody is looking for innovation now and new solutions. This is very good for nature because everybody is now proposing vegetal facades. Some years ago, we proposed that, and people said we were dreaming, but now everybody needs to do that because it’s a challenge. We made an example and now people want to have plants on the rooftop of the building or terraces to practice urban farming and so on. The city of Paris organizes some competitions for the making of urban farms on big roofs and this means that we gave an example they learnt from. The practice is changing in terms of scale – from small buildings before to whole parts of a city now but they are all collaborative projects between investors, developers, architects, artists and so on. It’s very different and exciting too.”

Cédric Ramière: “More than 50% of the architectural offices in France are ‘one-man shows’ – they consist of only one person working alone. In other countries like England it’s the contrary…”

Claudia Staubmann: “It’s the contrary; it’s a much bigger dimension.”

Cédric Ramière: “…big firms with a lot of competence. We think we should organize ourselves in this way in the future because if you want to face the new market by yourself there is a lot to know.”

Claudia Staubmann: “I’m not French, so I see it from the outside. I would say it’s still about haute couture; the architect is still working as a craftsman because, you know, in 50% of the offices there’s one man and he’s doing everything. For me that’s the French architect. There is so much danger because you cannot know all these rules and it’s quite complicated today to make a building.”

Cédric Ramière: “You cannot do big projects.”

Claudia Staubmann: “France is one of the countries with the biggest rules; there are really lots of regulations in construction.”

Cédric Ramière: “Norms. When you’re alone driving your office it’s almost impossible to face all the norms and get to know all of them. So, most of the people who work alone do singular houses – this kind of thing.”

Phillipe Croisier: “We are lucky in my country because we are under public command. France is extremely lucky for that, but we have to know that it is getting smaller and smaller each year and private investments are gaining ground. I hope that our state will continue to defend architects, but I’m not sure about it.”

BELGIUM

Basil Graux: “I work together very closely with urban planning and the cities – the vision they have. We see a lot of change in Belgium – the vision they have now is completely different than the vision they had five years ago due to the [name of regulation?] – one of the organs that was put in fifteen or twenty years ago. It’s really important for us all to change – the clients, the architects and the promoters – to get this knowledge and understand that all these elements will be necessary to have a good environment to live in.”

THE NETHERLANDS

Jeroen Shipper: “It’s getting out of the crisis, which was quite long, the crisis was between 2008-2016, almost more then 7-8 years. It reflected in a way that was less initiative from professional parties, so there were not many building initiatives, everything was frozen. The good think is that it was a lot of popular initiatives, a lot of small initiatives coming from down-up, but if you see, for instance in a city where we work and live, in Rotterdam, there are so many new small initiatives that re-fight the city that came actually from the crisis, this was the good thing, so no big buildings, but a lot of small initiatives of re-furbishing all the industrial warehouses. And it was easier in the city of Rotterdam where the ground is much cheaper than in Amsterdam, so you could say this is a bit of a bold remark, but the Rotterdam partly benefits from the crisis because it became more small scale livable popular initiative city. That was the nice thing about it. And now we see it because, when everything was frozen we had a deficit, we built too few housing units, so now it is a need for housing, we have too few houses in Holland, do now, you see, there is an over- cooking market that we need to deliver and to build housing units, and the most important thing now is to do it properly and not in speed, there is only big and a lot, but not good.”

Reinier de Graaf: “ Yes, architecture is relevant, but maybe not that relevant as it likes to think of itself and maybe more relevant on the biggest skeptic things. But for me it’s not about being relevant or irrelevant. What I find strange is that, because the only thing I have tried to prove, and I consistently try to prove is that architecture is not independent from the forces that shape it, that is saying something very different than saying that architecture is irrelevant, it just means that it exists in a relationship to other things, and it’s very weird that the architecture profession oscillates between a kind of an extreme confidence and an extreme hubris and then assume that the autonomy is questioned even more when people disintegrates into kind a form of self-denial and I think that is unhealthy, and I think hubris and inferiority are strangely linked there. I think if you trace back that’s also the point as I said in the lecture, we’re educated in a modernist era which we think is an everlasting era of universal truth and I think is a historic period like there have been other historic periods and in a way architecture was always shaped by other forces and now it turns out that even modern architecture was shaped by a particular economic reality of the given time, that is also not everlasting. What I think is interesting is that it was just a test we did, overlaying this pickaty graph on the architecture production and you discover parallels and all of the sudden you can explain certain inexplicable stylistic twist that seemed to have happened out of the blue and taken the whole profession. The whole transition from modernism to post-modernism is never explained inside the architectural discourse, it is something that happened, most modernist thought it was inexplicable that it could happen, why did it happen, it was insane, and so this is the way it has been discussed and I think you can actually trace back the moment from modernism to postmodernism as a specific economic moment that buildings from functional instruments become property, they became kind of an asset class, it’s the same moment that the term “real estate” started to become very prevalent. So, it’s part of an economic reality that it has changed and if that is not an enough convincing explanation there are certainly historical interpretations that have existed.”

Xander Vermeulen Windsant: “In a way, architecture in the Netherlands is famous because of its liberal design attitude. As architects we have a lot of liberty to design the way we want, but, and this is important, this in part possible because we’re not legally responsible for anything. Apart from really stupid mistakes, we are not accountable for problems in construction. The upside of this is that we can be very free in our thinking, but the downside is that we are very easy to be put aside- we have very little power in the process. Apart from a couple of well known ‘stararchitects’, most Dutch architects find themselves in a very fragile position. And, but this is not something exclusive for the Netherlands, architecture is rapidly reduced to project marketing. The products form our liberal, avantgarde – based design tradition, the fancy forms, bold color palettes and extreme structures are nowadays sought after because they offer an interesting commercial distinction – it is a fancy thing. I’m not so optimistic about the state of architecture in Holland, because when we can design anything, doing something crazy becomes the norm. There’s no restriction, there’s no need for an inner logic anymore, we can do anything. I think we will have to find a new inner logic, to put new constraints on ourselves in order to do something meaningful again. The main issue I think, should be projects, which are not just about building houses, but which are about creating special environments, in which social issues, environmental issues, energy issues are integrated into. From this comes a new logic of the project and then we have to think how we are going to build this new environment: public spaces and buildings alike. So, we don’t start from the logic of construction, but we start from the logic of an issue we want to solve, and then we’ll try to find the most appropriate way of constructing these solutions”.

GERMANY

Roland Bechmann: “In Germany we have good architects, we have a very strong school of architecture which is being seen in the entire process of the design and focuses also on the later phases of architecture. They can provide very good detailing. We are struggling a bit of course, as in every country, because architecture is driven by economic needs. City governments and governments in general have to understand that this is not only about economics but in the long term really about sustainable concepts and we have to find solutions. It’s not one single project we are looking at but really the entire system, the entire city. There are public investments, but the majority of projects are of course driven by private investments. The projects with public investments are typically very slow and make it difficult to provide a high level of quality. Private investors actually have the chance to go one step further beyond something we’ve seen before, but they’re hesitating due to economic reasons. I think we need more competition for projects, and we need a good combination of investors and architects.”

UNITED KINGDOM

James McElgunn: “I think it is about understanding the environment where you are working. You cannot just export a building, that kind of a London response to Mexico and expect to work. There are different regulations, different construction industry, different procurement values. So, I think the biggest challenges are to understand where you are going, understanding the level of sophistication of the construction industry and what can be achieved. At the moment you cannot achieve the same levels of building in certain countries that you cannot meet in Europe, particularly in north-west Europe. So, it is being aware of those. In the United States it might just be a question of understanding how the unions work, because running a mechanical and an electrical plant through the steel work does not work. Because the two unions don’t want to work together. They want to work in isolation. In UK is it very common for us to thread structure, mechanical and electrical plant together to save build up. In New York you cannot do that. Well… you can do that, but it adds time on to the program and therefore it is not worth it. So I think the biggest challenge to export architecture is not trying to just export it, it is trying to take a model, take an idea and burying it in some place and then allowing it to become quite local, to react to its local environment.”

Paul Bulkeley: “The quality of architecture in United Kingdom is increasing, but it’s not increasing across the majority of the buildings that the most people come in contact with. So, one of the reasons we as a company chose to work in housing is because housing generally doesn’t have much architecture involvement, so we want to bring architecture thought to something that ubiquitous as housing. So, the quality of Architecture is slowly rising, is slowly increasing and I’m slightly concerned about Brexit, whether Brexit is going to bring some challenges. I think there are short-term concerns about how the industry deals with supply chains, labor those kinds of issues. Longer-term I hope that the architects in Britain don’t look in-wards too much, I mean I find it really interesting coming here and hearing what is happening all over Europe, I think it would be a real shame if British architects would not work across Europe. The positive is that we will probably look to the rest of the world more, so I think we will probably see British architects working in other parts of the world more than they are now, because they would probably work less in Europe, hopefully it’s both. Hopefully we continue to work in Europe, and we look beyond.”

DENMARK

Julian Weyer: “…It is in a weird position in a way, much… we had that fantastic lecture about the utopia, the dream of the architect… at the same time architecture is very much under pressure in Denmark because we are exposed to exactly the same amount of market force, exposed to the same political debates as any other country so in a way it’s this weird duality between architecture as a profession, but especially architecture as means in society, having also high values, people are genuinely address…..regarded as something which is important but on the other hand, we are under pressure in the same way as literary everybody else when it comes to how do we work with the market forces, both the private and the public sectors, both are grappling with the level of complexity and their different agendas so it’s not that everything is easy and utopian in Denmark.”

Heechan Park: “The biggest difference between South Korea and Denmark is density. The easiest way to understand is the numbers, in European countries I would say the density, which we call FMR, the building referred to plot, is about 1 or 2, but in South Korea we have a project which is 9 (900 %), which is totally non-comparable I would say, the way we treat architecture and the way we deal with architecture should be different. But of course, we try not to forget what’s the principle of our work we want to create, we try to find something common because we are doing the main projects in Seul, Korea.”

IRAN

Kamran Afshar Naderi: “Architecture should be a language. I think hopefully the things are changing. Architecture remained for a long time confined within the limits of visual perception and meaningless forms. In Iran, the architecture language used to be very close to the spoken language. Contrarily to the western civilizations, we accepted the language as the dominant media for transferring any kind of idea. For instance, when, during XVI-XIX century, the European voyagers came to Iran, they produced a great amount of illustrations showing people, monuments, nature and so on. Contrarily, our travelers left only written descriptions about what they had seen during their travels to Western or Eastern countries. Another example: even today in Iran property deeds of the buildings don’t contain any drawing, everything is explained in words. Iranians created outstanding buildings without using drawings. The language was accurate enough to describe an entire building without the necessity of drawings. And architecture was organized such as narration. Narration was an efficient mean of communication and therefore instrument for conceiving architectural ideas.”

Habibeh Madjdabadi: “In Iran it is still possible for the architects today to do craft art. The hourly wage of workers is not so high and not higher than using advanced technology.”

THAILAND

Sirapa Supahalin: “I am considered a young architect, young designer, but there a lot of projects, those small projects that people can afford. But sometimes they don’t have so much money that they can afford big names of architects, so they approach young architects so there’s many opportunities for that too.”

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Carol Ross Barney: “It’s really interesting for me to come to Bucharest today and talk to my colleagues and they complain that their clients don’t appreciate architecture, I think I’ve had that conversation with several people. They go, oh in Chicago you’re lucky because architecture is so important there. And here nobody thinks about architecture, and it’s not valued, I think that every architect feels like that and if you don’t, you’re not trying hard enough because that’s always more. In Chicago, the good news that we do have a tradition for innovative architecture. I hope we don’t lose it, I mean its part of a civic culture, social culture that Chicago benefited actually from the last two centuries, and I hope we’re not one yet, and I hope we don’t lose it. We still fight the battles, there’s always like Oh my God, really, you’re gonna make me do, that didn’t work when we did it last time, you’re really gonna make me do it again? But we’re lucky in a lot of ways, we’re an exporter architecture, on the other hand we kind of a mystery city. I mean everybody recognizes that Chicago is a world city but they kind of go: where is it? What kind of work class city are you? And people recognize the name but it’s not always. People who go to USA go to New York, and they go to San Francisco and they go to Orlando, and your kind of missing most of the country. It’s not bad, I think a lot of about it. Architecture, in general is practiced at a very provincial level. We have a lot of ideas that we can gather now, because communication is super powered but when you actually get to building a building you’re still building it by hand and in the mud, so it’s still very provincial in a lot of ways- that’s gonna change too! You’re still gonna be dealing with the mud someday. The mud is still there, but I think the way we build it by hand, in fact Bechman from Sobek was just talking about that, when showing some pre-fab modules that they designed for refugee housing in Germany. You go, that’s really smart, you know.”

TURKEY

Kerem Yazgan: “There have been enormous constructions going on for at least ten to fifteen years. So, architects are trained like football players in order to make lots of sketches and buildings. I think this is helpful. However, in my country, I’d say the most unorganized thing is the master planning. There are good buildings, but not a master plan. Architects now are much more international, they work very much for the city, but when it comes to the master plan, it’s something else. I think Turkey should change this approach and get planning for the cities.”

GREECE

Vassilis Sgoutas: “It is a very difficult question, because we don’t rule the game. We don’t define the system, because our role is secondary, so it’s very difficult to say what I would change because if I could change, and that’s your question, well, I would encourage very much the highlighted work of the young architects and as far as the change in the public opinion, because that in the end will influence things, one way would be to actually remark buildings that have received some distinctions, any distinction, not necessary grand prizes or whatever, and put a plaque on the building to tell people that this was one of the ten awards of the SHARE conference, they may not be great buildings or top buildings, but there they are, and maybe that would help somebody think before it re-designs or demolishes that building.”

Rena Sakellaridou: “ Well, I don’t know, I’ll talk about Greece- it has fluctuations, when there were fewer architects there was a privilege to be an architect, it was important. Then architects- we had a lot of architects- we lost our relevancy. I think architecture becomes important again, and that’s very good, and people are more open to good design and architects, which is very good. We have a very important tradition and we live with that, but when you live with something, when you can see that every single day you want, you live with that, you breath that but we don’t think of that. It’s part of the air. In other cities, for example in Europe that have beautiful baroque city centers, why should they have tall buildings in the middle of a baroque neighborhood, you don’t need that. You see, tall buildings are very interesting, they have great optics, they are very good for developers, I love American cities, I love that, I love all those tall buildings, Manhattan.”

POLAND

Krzysztof Ingarden: “I think we’re living in very good times for architecture. I would say our recent period in Polish architecture, but not only Polish, is dominated by great optimism and dynamism. Big diversity as well. It’s a period which can be compared to the period after the First World War, when our countries gained independence – there was this big optimism to reestablish these countries and many architects and art historians were trying to find a national style or the source of traditions. I wouldn’t say we have a national style now but is very interesting that each geographical region has its own idiosyncrasy or specific features and also specific ways of treating materials and constructing a timber building, for example.”

Ewa Kurylowicz: “I think architecture has improved a lot. There was a big movement, Poland joining the European Union in 2004 along with the Public Procurement Law, which is not that good (the interpretation in Poland was not too good and caused lots of trouble) – and then the money started to come in. The public investors received this money and there were a series of decisions in order to catch up with the years that have passed. Before 1989, as in Romania, there was a different political system, there was one investor – the state and the rulers from one single party and they were doing whatever they wanted. There was no experience and architects didn’t know how to run private offices. We were lucky in a way because we started our private activity designing churches – there was something called the Church Boom in Poland; religion is a really big thing in Poland – it used to be bigger, now it’s slowly fading away. The Communist Government knew the power of religion even though it was not officially stated, and they allowed building churches. That period lasted for fifteen years, from 1975 until 1990, when we had more than 1500 churches built in Poland in different places.”

Andrej Bulanda: “The state of architecture generally speaking is parallel to the general economic situation, the spirit of the nation, which is right now, from my perspective, not so good- due to some political changes and populist movements which are taking over in Poland. It is very difficult to make this type of generalization, but from my perspective I think that after a clear enthusiasm of the new opening in the ’90s on every level, and especially in architecture, because architecture in Poland was a state oriented business, so that the recreation of the free independent profession took some time, but everybody was enthusiastic about it, and now we entered a state of routine, with problems which exist everywhere, which means national competition of youngsters which are new-comers to the profession, and they are enthusiastic, hungry for success, cheap, and this is sometimes very difficult competition to take, but this is natural, everybody was young someday, this is nothing wrong about it because this is a stimulation for growth etc. Another problem is the diversification of the scale of the office, because when we started there was a small office, then we grew up and the office became bigger and bigger, and suddenly something collapses, which means that big offices are getting bigger, and the middle group of offices, which is well-established medium-size companies, or small companies they are having very hard times because developers and clients are disappearing, and the big clients, big corporations are going to big companies, and then there is the market of small, unprofessional or semi-professional developers and clients who are tending to- they are not able to judge the quality of architecture- so their natural tendency is to go to cheap stuff, which makes for the offices like mine the situation a little bit difficult, because we are not in a very familiar commercialized type of architecture with big business, we are trying to do public buildings, and it depends on the general economic situation of the country. All public commissions theoretically in Poland are done through competitions or through some kind of tender in that or another form of design built, but in Poland the situation was that with open funding from the EU, everybody wanted to do something because the money is on the table, not necessarily they can define the real need. If there is money, we have to build something to take it. The problem is, this is on the other hand, this is the ladder of growth, but on the other hand some of the projects are not well planned (nobody counts exploitation, cost of the building) and some of the buildings which were finally built they are badly operated, there’s a lack of fund for proper operation, so they are ahead of time, ahead of the national status of the country, they are not needed, the trend was to build swimming pools and there are water-parks in every small village, they are empty today, This is like in Spain- they overbuilt. Firstly, on the governmental level the needs are not well defined, and there’s big pressure to use the money.”

SLOVENIA

Dean Lah: I wouldn’t say that there is a Slovenian specific characteristic architectural language, it is not because, to be completely honest, we have now two schools of architecture, we used to have only one. But the other one is very young, it’s still 5-7 years old and it is still trying to figure out its position, but it’s going to be different and original, and I would say that if you look to the works of all ahead Slovenian architects you couldn’t connected two schools, like usually, so it is really the result of this unbelievable time that we have doors. So, I wouldn’t say it is the architectural language that it’s different, but it’s maybe the- I don’t know if I’m allowed to say this, but the freshness of the approach that was different. Architecture and politics have always been bound together. Normally we always focus on the fighting part, but from this case you can also see that there is opportunity in that. I think that no fighting should be just fighting. All fighting should be about understanding and trying to adapt, and out of this, if everybody tries that, it may come really good results.”

HUNGARY

Tima Zoltan: “To build up the creative work on the Hungarian tradition, or the historical architecture, there is quite a big difference on the two sides of approach, one is local organic architecture represented by the most famous, Makovecz who died eight years ago, but his followers are still keeping this approach on the scene, and the other part of the Hungarian architecture is trying to follow up the international trends, but although incorporating the traditional Hungarian layer of thinking. That’s what I also think, that we have to greet up-to-date and state of the art buildings, but we can never forget where are we coming from and all the knowledge which is maybe not formal knowledge but the content, the technologies, the simplicity of the people, this we have to bring forward and build into our way of thinking.”

Hatvani Adam: “It can be challenging for architects- I can talk about the recent situation- that many people left the country, also in the field of architecture and also in construction, and something that we have to face is the lack of workforce, and this is challenging really for architecture offices. One other thing is that are plenty of projects in the same time: office, residential… it became a question how to do this, so when the crisis was ten years ago, it was totally the opposite situation. But this may be a technical question, but it’s important and that means that all the deadlines are very short and the demands are more and more serious, but, like being a giant without arms, or half-arms, but I hope it will come…There are like invited tenders for pre-qualified offices which some of them are […] some of them are well-established architects, so most of the job is not landing by the brighter side of the profession so I can tell you that there is not too much competition, but still we have possibility to make competitions abroad.”

Gabriella Sajtos Grand: “It’s very difficult to answer the question about the state of Hungarian architecture, not the question but the position of the Architects is difficult in Hungary because it’s not always the quality of work which is the key when the client chooses an architect, but connections and many other factors that are not related to architecture. So, for a young architect is not easy to start here in Hungary.”

SERBIA

Goran Vojvodic: “I am not the right person to define what is going on with architecture in my country. I would like to change a lot of things. You can see that everywhere – there are good things and there are bad things – not just in architecture. The problem in my country is that there are no educated investors for sure. Economically speaking, we are not in a good position… there is no interest. I do not speak about the difference between a small project and a big project – the question is if you have an educated investor in front of you or if he is willing to learn. Sometimes I think and I’m telling this to my students that architects have different obligations and one of them is educating their investors.”

Ivan Raskovici: “I’ve been Chief Architect of Banja Luka since September last year – not that much, seven months. Something that is still visible is that people received me excellently within the municipality and administration. I have nothing in Banja Luka – no family lines, nothing – I was recommended by some people and that’s how it started. There is a Japanese story about a warrior in shining armor. He lent his shiny armor for a battle to another man and he was killed instantly, while he lived. So, you see that a shiny armor – people looking at you and trying to find out your story. It could be very useful if you know what to do with it. My position is advisory, so I didn’t have an exact power – I’m the mayor’s adviser.”

Vesna Cagic-Milosevic: “In the earlier Yugoslavian space, architecture was really different in contrast with the present. Everything was owned by governments and it was some kind of humanitarian planning, everything was oriented to people and their needs. Now it’s oriented to the personal interest in money; it’s not only about money – it’s not politics either, but the influence of politics. We have problems in this area. The architectural profession is not totally regulated. We have some kind of regulations but they’re not similar to other regions in Europe. We don’t have a chamber; we only have our organization. We have the Chamber of Engineers and we must be a part of that due to licensing restrictions. There is no Chamber of Architects, but we’ve been working on that for the last few years, so I hope we will succeed. ”

BULGARIA

Angel Zahariev: “I can say that we are still in transition. This period of socialism is still deeply reflected in the work of the architects. We have experienced a very big gap between the generations that were educated in these times and the following generations. This gap occurred maybe ten years before me. There were some years after the changes in the ’90s – there was a sort of mess in the society. We’re still in a constant transition because we started from zero, let’s say. We started learning how to do contemporary architectural practice, but we were just following some models that already existed somewhere. We were looking at what was going on in Western Europe and then applied it.”

Maria Baleva: “I don’t think architecture is very aesthetic, it’s really profits driven. There are only a few small good examples, which are more present in the private sector now. People have the right attitude, they want to change something for the better, but we still need to change the mentality and convince people that even large-scale projects have to be important for them and their surroundings. I think it’s a long process that’s only at the beginning.”

ROMANIA

Adrian Cancer Zeana: “One of the most painful issues is related to the relationship with the authorities and how you manage to bring a concept, regardless of scale, to authorization so that it is put into practice -this is a serious problem now.”

Andrei Șerbescu: “The state of architecture in Romania? Hm…I wouldn’t put the blame directly on the clients: before the clients are the architects. Sometimes is it possible to educate the client, and sometimes it’s not. We had the opportunity of meeting already educated clients, which is something quite unique in Romania but we had this opportunity and I think they made possible some of our projects… but we also met clients with whom we were unable to discuss with and develop some ideas together. It’s a mutual training actually, we would speak to them about our things and they speak to us about their own things and from putting them together these views result this mutual training. But before the clients… I think there are the architects.”

Marius Miclăuș: “If I refer to Romania … I think I could refer to the scale of the projects … from the scale of the city to the scale of the architectural object. I think we must first learn how to use public space … then about architecture that generates communities or relationships between people… so that means engaging with a multidisciplinarity side that should be in the profession.”

Sergiu Petrea: “The problem is that being part of the European Union, the issues are nowadays global but simultaneously local. Indeed, from the romanian point of view I could say that the budgets for design and those allocated for construction are much smaller than in many other countries. There is no a legal framework that could help us as we have a very old and controversial legislation. At the same time I think that we should be very concerned with the issue of energy performance and global warming, because through legislation and directives we will be forced to follow certain steps in this direction in the near future. “

Adrian Spirescu: “In my opinion, a problem that is not only in Romania is the fact that the profession seems to lose its importance and relevance. It seems that the architects of the past were those refined and cultured people whom to which the world looked with great respect, appreciation and their point of view was taken seriously all the time. Now it seems that we have taken a step back. I have read many specialized commentaries in this sense, many socio-professional analyzes, and there are many explanations a part of them referring to the fact that technologies have evolved, the fact that a home can be done alone with the builder … “

—

Follow us at share-architects.com to stay up to date about the evolution of our editorial project “Designing the Profile of the Future Architect”, to be launched this 2019.

Why so?

We have so much to SHARE!