Interview with Ken Yeang for share-architects.com

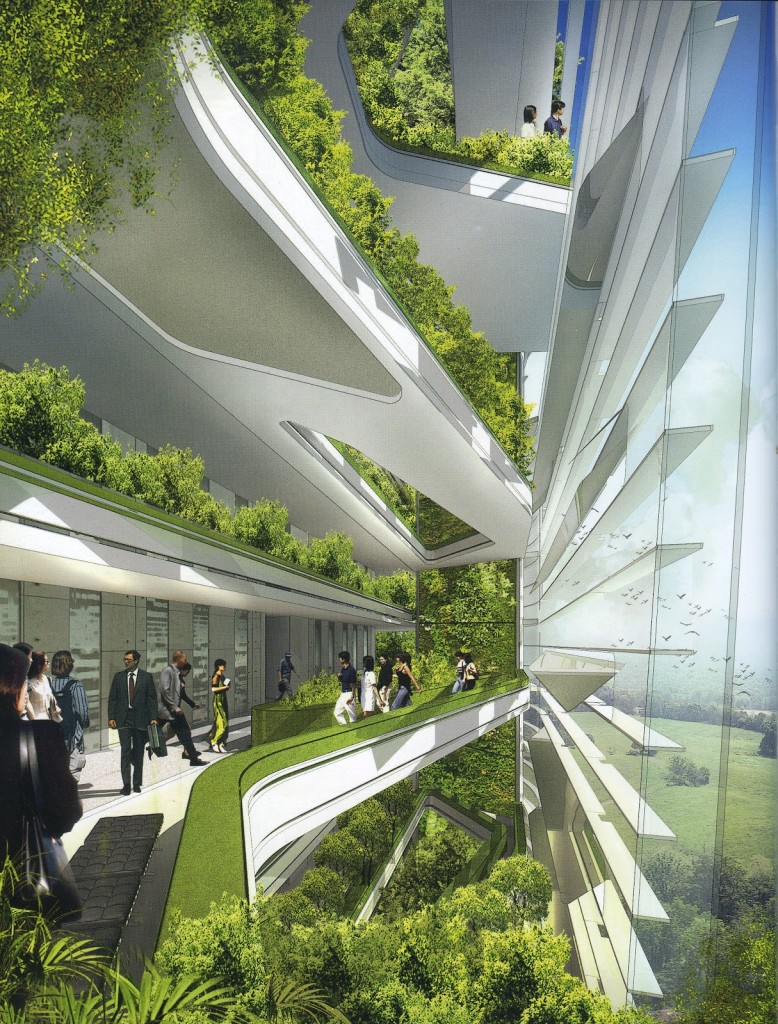

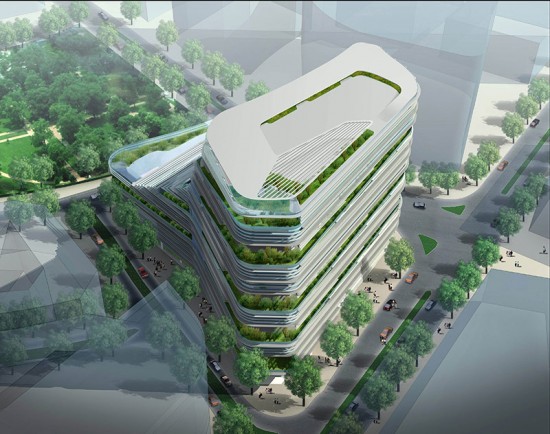

Malaysia-based Ken Yeang, named by the Guardian newspaper as “one of the 50 people who could save the planet”, talks about ecology and his sustainable architecture with share-architects.com. His award-winning portfolio includes Singapore’s National Library, Menara Mesiniaga, The Roof Roof House and Solaris Tower.

The work of Ken Yeang, one of the pioneers and true visionaries of sustainable architecture is focused on the disciplines of ecology with architecture. Born in 1948, Yeang studied architecture and ecological design in the United Kingdom and the United States and in 1974 Yeang received his doctorate from Cambridge University with his dissertation titled “A Theoretical Framework for the Incorporation of Ecological Considerations in the Design and Planning of the Built Environment.”

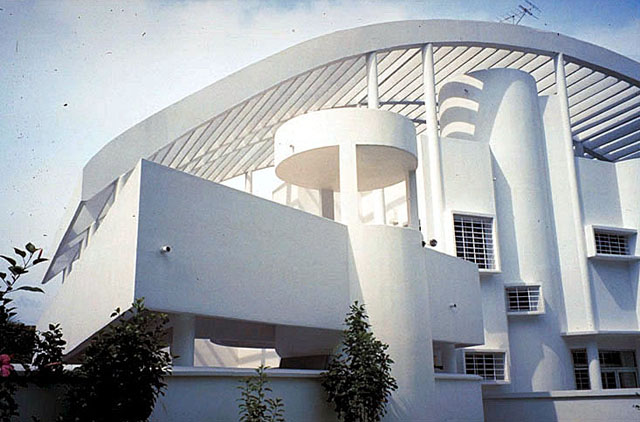

Yeang starts designing his ecological structures by first responding their locality’s climate and then its ecology. He refers designing with climate as ‘bioclimatic’ design which provides the starting basis for the subsequent inclusion of the ecological aspects to be ‘ecological’ buildings. Bioclimatic structures are low energy and operate largely in the passive-mode, meaning that the buildings’ have features, such as natural lighting and indoor climate systems which are the result of careful integration of the structure with the surrounding climate. An example is Yeang’s own home, the Roof Roof House built in 1985, which incorporates many of these bioclimatic ideas. The building’s distinctive dual-roof design filters the tropical Malaysian sun and provides shade to the house below. Its unique curvature was designed to let in daylight from the east in the morning, while deflecting heat and light in the mid-day and early evening sun. Additionally, the Roof Roof House features a unique system of cross-ventilation that is built into the geometry of the plan and built configuration which allows the natural wind-flow to keep the house’s interior comfortable.

P.E.: Who inspired you to become an architect? Are there any particular influences in your early career?

K.Y.: When I was about 4 years old my father was building a house for my mother and he used to take me to the construction site. That was my first experience of construction and architecture. When it was near the time to go to university, my father wanted me to become a doctor but I did not want to be a doctor so I agreed with my parents that I will be an architect. I had three uncles then who were already architects and one of them went to the AA School and so I attended the AA School in London.

P.E.: When you graduated from the AA in London and Cambridge, there were no digital tools back then. How did these change the way you work and your later design philosophy?

K.Y.: We had to train our people to work with AutoCAD and then buy the computers and the software. The costs were a huge problem for us. Then we found that it speeded up the drawing delivery process. It took us four years to work completely in AutoCAD and by 1995 we were fully CADed. Of course we did not stop there. Our systems are now BIM.

The way we worked also changed considerably since when we started. When we started the office in 1975 and I would go to meet the clients after one to two hour flight, then after spending half an hour meeting the client, and plus the waiting time, I would fly back, whereupon my day was gone. In 1982 came the fax machine. I could fax the client and speak on the phone to talk about the design and any changes. And so I did not have to spend a day going to meet the client. Then came the internet in ’89-’90, and CAD in 1995. Now we have BIM, social media, augmented reality, and CFD (Computerised Fluid Dynamics) with all sorts of environmental simulation software. The work climate has changed. We had to keep ahead of the times.

P.E.: Can you tell us about the house you built for yourself?

K.Y.: The house is down this same road where my office is located. I began designing this project in 1981. For this residential estate, we did a standard design for a standard lot, but then we had one house lot that the standard design could not fit, so I told the client I will buy this lot from him. The client also had a shortage of cash for the project, and we bought this office building from him. By 1984 I had designed the house and at the end of the design stage we put in the second roof in the design. The house was completed in 1985.

P.E.: And now do you still live there?

K.Y.: Oh, yes I still live there! But an interesting fact in my life as an architect was that my very competitive architect colleagues used my house’s design against me back then. They would tell clients, “…look at Ken’s house, if you use Ken as your architect this is what you get, an unconventional design, but if you hire me as your architect, you’ll get a conventional house..” So they used the house against me. Fast forward 30 years and by 2015, these same architect colleagues would refer to the house and say: “…this is Ken Yeang’s house ..Ken Yeang was ahead of his time..”

P.E.: You are concerned about ecology, sustainability and green design in your buildings. What role does poetry of architecture play in your work? Could you please tell me more about the immaterial part of architecture and how you handle light and space in your buildings?

K.Y.: Light is very, very important and for example, my house has a very bright and cheerful interior space with no internal glare. It has large windows at the ground floor on the north, south, east and some on the west facades, and when I wake up in the morning I get a bright magical space. The glass wall facing the swimming pool lets in the sun reflected from the swimming pool and I see the water moving on the ceiling, which is a nice and pleasurable feeling. Natural cross ventilation of wind is important, and here I can adjust the wind-flow across the interiors by adjusting the external wall openings, depending on where the wind is coming from.

But let me tell you a little about I feel about the poetry of architecture. To me, a work of architecture has to address the following factors: the first is ‘function’ – it has to work, and work well otherwise it is useless. Second is that it must meet the usual ‘criteria’- it has to meet the governmental building requirements, address client’s costs and budget, be delivered on time, be of quality construction and meet other criteria including being green. The third factor is that it must be ‘beautiful’, and this is of course very subjective, but this is where the poetry comes in. The forth factor is the most important one to me – it’s the happiness factor. The architecture must make people happy. If for example, you do a house for a family, you can actually positively transform their lives. You can make them immensely happy. Similarly with an office design, you can make its users incredibly happy working within it.

P.E. You can increase productivity

K.Y.: Yes, but architecture is not just about increasing productivity, but about happiness. Productivity has to do with money, but happiness is what architecture is about. Before we start a design, we ask ourselves: ”What can we do to make the users and people happy? What are the things we can put in? What do they want?” Some people call it ”liveability”, but for me it is all about happiness.

P.E.: Is green design a movement, style or something that we should incorporate from now on in every building?

K.Y.: Green design is a must-have. We cannot run away from it. It’s an obligation to us to conserve the natural environment. In the last two hundred years since the industrial revolution, we forgot about it. We denied nature. And suddenly we realise that climate change is affecting the planet. There are raising sea levels, the air is being contaminated, with climate change we find places that where hot became cold. We have to design for the future of the planet. Actually it may be a bit too late and it will become worse if we do not take imminent action. We have maybe 50-100 years left to repair what we have destroyed.

In other words, design has three dimensions: past, present and future. Maybe 10-20 years ago we designed preventively for the future, we designed in such a way so as not to affect the future environment. But now with so much damage having been inflicted on the planet, we have to design to also to repair the past, and not to affect the future. 20 years ago we did not have to address the past, but now we have to.

P.E.: What is the next big thing in architecture that we need to focus on?

K.Y.: Well, that’s a lot of things we need to focus on. The problem with a lot of architects is that they came into sustainable design a bit late in their architectural life, and so many do not have an adequate background in ecology. If you have a background in ecology you realise that designing ecologically is complex and there are lots of factors to address. To me it is important to biointegrate our built environment ecologically with natural environment, and this is not simple. A lot of architects today think that the accreditation systems is the end-all to green design, having done a LEED Platinum or BREEAM Excellent building. They do not realise that there is much more than just accreditation.

To me there are three ways to design ecologically: nature-centric, techno-centric and antropo-centric. Anthropo-centric means you give importance to people, people have precedence over nature. Techno-centric means you give importance to technology, which for example is what most accreditation systems are about. Nature-centric is when you give priority to nature and to me nature-centric design is the starting point, and not the techno-centric nor the anthropo-centric. So the next thing to me in green design is ecology, how to create our built environment and our production systems to be ecologically effective and to do no harm to nature.

P.E.: What do you think about standards like BREEAM, LEED etc? Is that approch still valid?

K.Y.: Well, there are two ways to look at standards. It should be performance-based instead of prescriptive-based. What’s the difference? Prescriptive means that you set a standard. Performance means you set an end-goal. Prescriptive is easy to achieve the standards, whereas to achieve 100% performance goals is difficult. To be good in anything there is no limit, and we need to seek to advance from good to great. Performance has no limit and that is our main objective.

P.E.: What about the clients now that there is so much awareness about green design? They are pushing harder for their contractors and architects to include it? In your office you propose the clients a green approach or do they come to you because they know you are doing this?

K.Y.: 60% of the clients come to us because they just want an architect’s service, and 40% of them come because they want a hyper green design. I think this 40% is increasing.

P.E.: How much important are the prizes and recognitions for an architct?

K.Y.: For me, an architect must do five things: He has to be unique and different. Secondly, whatever he does that is unique must be relevant – if it’s unique but not relevant, then what is the point? Thirdly, it must be topical – it should address current issues. Forthly, it must be credible – people must believe you can do it. And finally, it must be motivating – you must make people extremely excited about your work and want hire you as an architect right away. If you are able to achieve these five things – uniqueness, relevance, topicality, credibility and be motivating- you have got the commission.

And so what do awards do? Awards make you credible. It means somebody somewhere says you do great work, and that you deserve to be awarded. So an award is defined in business as ‘third party endorsement’.

P.E.: What would be your advice for the upcoming architects who are reading this interview?

K.Y.: My advice is that if you want to be an architect, then be an architect because want to design, to create and to make things, and you are so passionate about it that you are prepared to take the stress and to accept all the trials and tribulations of being an architect. An architect’s life is very stressful and not easy for a number of reasons. First one is that being an architect is a cash-driven business. That means to get your fees, you have to do the work first, and only then will the client pay you, but unfortunately not always straight away. The faster you do the work, the faster you get paid, and that affects the quality of design because of the time given to designing. When the project delivery takes a longer time, it will be longer for you to get paid.

Second stressful thing about the business of architecture is that it is usually delivery intensely – you have to deliver certain things by a certain date and time. Now if for example you have several projects in progress in your office and you have to deliver something for each one, whether a drawing, a document, a phone call etc., and if you don’t do it on that specific day or time, someone will get angry with you.

Third is that it is a people business. You deal with people everytime and you have to be careful at the relationship with the others. You have to be nice with the clients, the employes, the authorities and everyone you interact with.

These are some of the reasons is very stressful.

P.E.: What is your ultimate goal? What do you want to be remebered for?

K.Y.: What do I want to be remembered for? I have only one word, ‘ever’. I want to be remembered for…ever.

Foto: Courtesy of Ken Yeang